Turkey – Poverty, Forest Dependence and Migration in the Forest Communities of Turkey

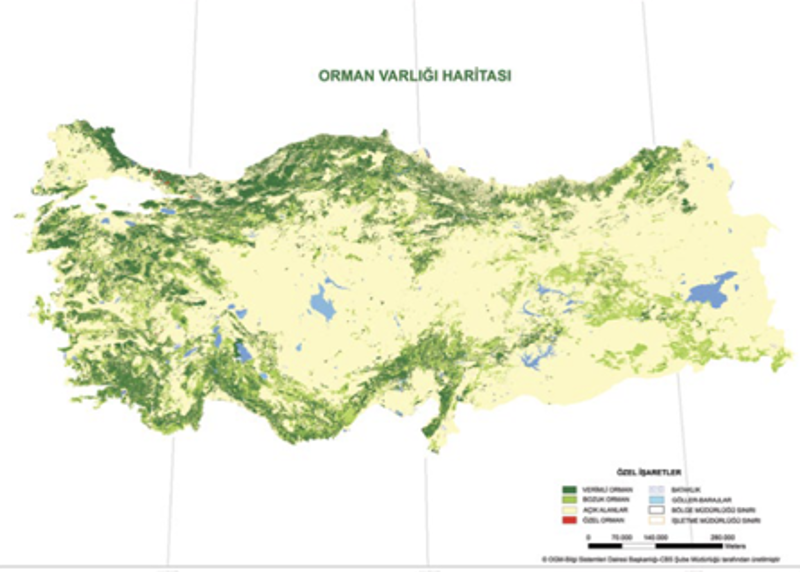

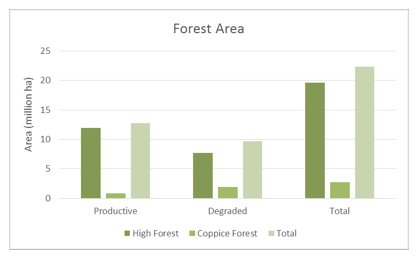

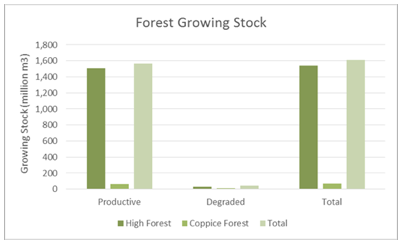

Turkey’s forests, covering about 28.6 percent of land area and accounting for 13 percent of the total forest coverage in the European Union (EU), represent an extremely important asset in both the domestic and international context. State owned forests (99.9 percent of all forests) generate over US$225 million in harvesting revenue annually and possess a rich diversity of non-wood forest products (NWFPs), largely unexploited, with great export potential to EU countries. Turkey’s forests play a critical role in conserving biodiversity, mitigating the adverse consequences of climate change, and supporting the livelihoods of over 7 million forest villagers (representing about 40 percent of the rural population). Forest villagers also represent a significant proportion of Turkey’s rural poor. Challenges to Turkey’s forest sector include low productivity due to inadequate investments in forest management technology and labor skills of local forest laborers, and out-migration from forest areas due to high poverty and lack of employment opportunity in these areas. Over the last 35 years, forest villager population has fallen from 18 to roughly 7.1 million, leading to a disappearing local forest labor force.

The Socio-Economic Household Survey of Forest Villagers (SEHS) was conducted by the General Directorate of Forestry (GDF) and the World Bank in 2016 to provide further insights on the livelihoods of forest-dependent households. The objective of the study is to assess the socioeconomic dimensions of forest villages, their forest dependence and the constraints to income growth in rural areas. This new data source collects important information on the socio-economic conditions of forest village populations, income generating opportunities, forest use and management practices, migration and activities of forest development programs and cooperatives. The survey builds on the forestry modules and the study explores the following questions:

- How dependent are forest villagers on forests, pastures and forest services (e.g. NTFPs) for their income?

- Do forests and related ecosystem services represent a pathway out of poverty, or does forest dependence entrench people in low income livelihoods and poverty?

- What are some of the specific determinants of migration (men, women? why did they migrate?), and conversely, what are the constraints holding back those who have not? Are these constraints skills-based or more structural?

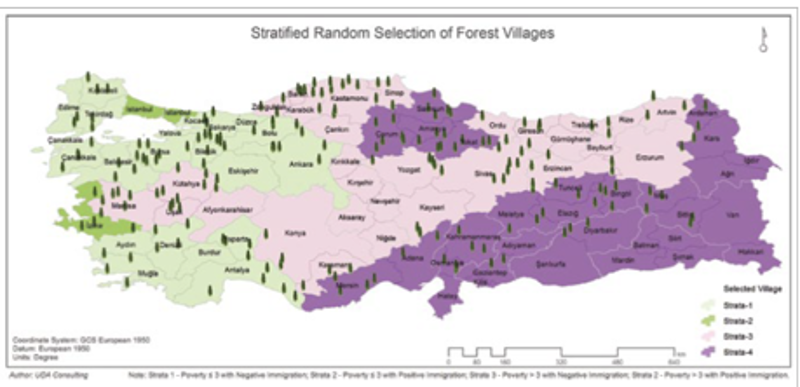

Methodologically, the sample design of the survey followed a two-stage stratification method. In the first stage, 203 villages were selected based on poverty and net migration rates. In the second stage, 2000 households were randomly selected. Policy simulations were also employed by the study. Household level information, including socio-demographic information, income generating activities, information on access to forest resources, and support from cooperatives, was collected using household modules. A village module was also administered to collect village level information, such as access to infrastructure and forest resources, and forest village development programs.

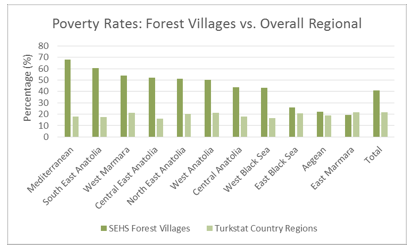

Results of the survey work confirm that poverty rates in forest villages are high with 40 percent of households living below the 60 percent of median income in the villages and poverty varies significantly across and within regions. Poorer forest-village households appear to be held back by their high forest-dependency and lack of income diversification. Forest income constitutes the largest share of income among the poorest households, with the lowest returns about 28 percent of a poor household’s income, compared to 8 percent of total income for non-poor households. Approximately a quarter of poor households receive income only from forests, compared to 2 percent of non-poor households. Further, non-poor households diversify more, and in higher return activities. Most often, these households supplement forest income with income from livestock, agriculture, and pensions.

In terms of the important challenge of out-migration from forest areas, the survey showed that growing out-migration is most prevalent among forest-dependent households, which poses a threat to the current forest management model that relies on forest village labor supply. Economic migration is a pathway out of poverty among forest village households, and its prevalence is on the rise. 13 percent of households claimed at least one migrant during the past 5 years, a number 2 percent higher than the 5-year period from (2005-2010), indicating an upward trend in migration. Moreover, a fifth of households (19 percent) with permanent migrants have no prime working-age members left at home.

For more information, please find the whole report here.