Gender

Men and women access, use and manage forests differs across the world (Agrawal 2009; Bechtel 2010; Mai et al 2011; Mwangi et al 2011; Peach Brown 2011; Rocheleau and Edmunds 1997; Jagger et al 2014).

- Overview Appreciating gendered differences in use and income from forest landscapes matters for interventions and institutional arrangements to be both fair and effective

- Country study: China – the study suggests that for the PRIME pathways to work for women, gender-specific actions to ensure that women acquire new forestry skills, benefit from more secure tenure, and take advantage of new jobs and markets are required

- Gender-related work funded by PROFOR include e.g. a portfolio review , an annotated bibliography and a report on Catalyzing Gender-Forests Actions

Overview

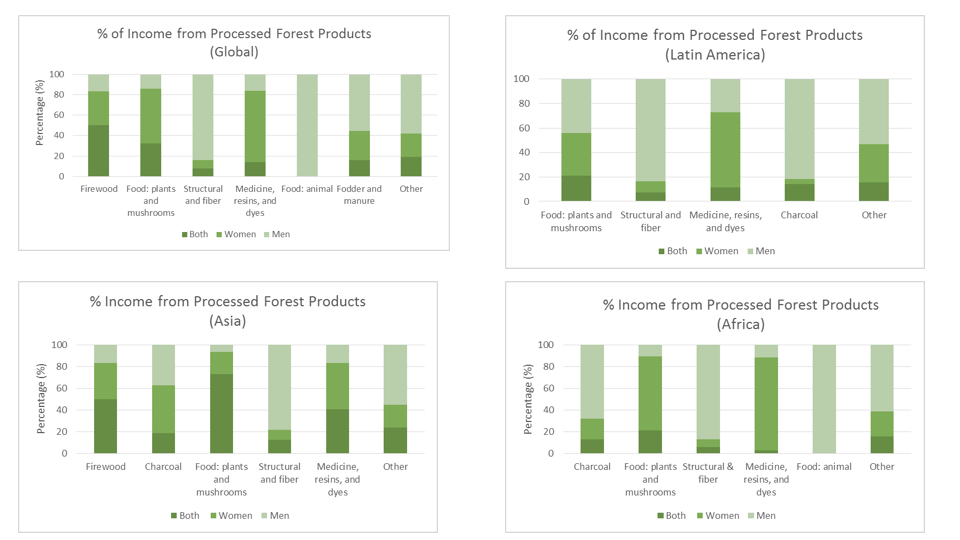

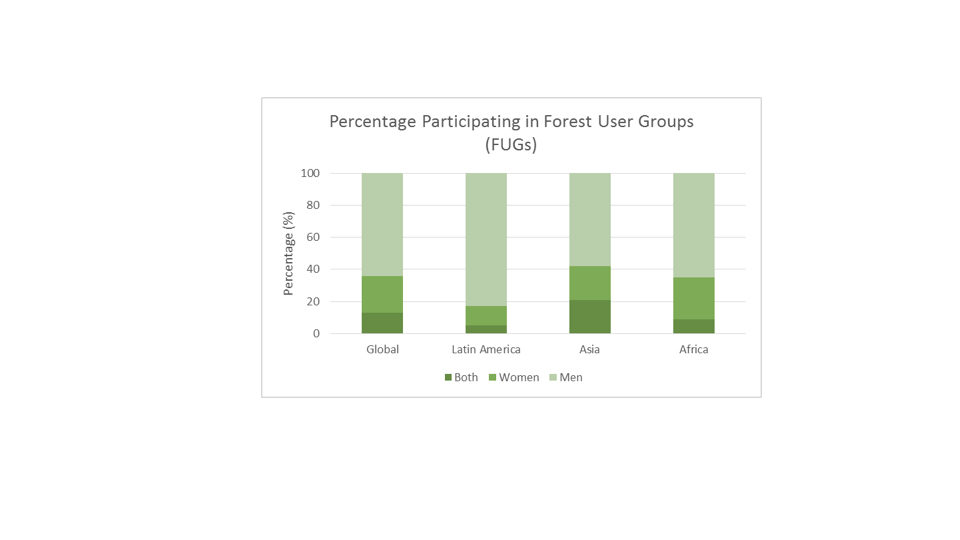

Evidence from e.g. the Poverty and Environment Network (PEN) global study points to distinct male and female roles in relation to the collection of forest products that vary across regions (Sunderland et al 2014). In Africa, women are the main collectors of subsistence-oriented forest products. In Latin America, however, men dominate firewood collection; and African men are more involved in this activity than often assumed. In all regions, men are more involved in hunting, wood harvesting, and minerals than women, which is not a surprise. But an unexpected finding is that globally, men contribute just as much to households’ forest income as do women. Persistent gender gaps in access to services, markets and value-addition activities, land and tree tenure, voice and agency, and hiring labor, result in forestry program outcomes that often marginalize women (Colfer et al 2016). However, appreciating gendered differences in use of, access to, and benefits from forest landscapes matters for both fair and effective design of interventions and institutional arrangements.

There are many constraints to achieving gender sensitive outcomes in forest and agroforestry efforts (Kiptot 2015, Colfer et al 2015). Common challenges across Asia, for instance, include: gendered norms and cultural prejudices that reinforce forestry as a male profession, lack of evidence-based research and gender-disaggregated data, limited technical capacity and budgets to implement gender-focused activities and women’s limited representation in decision-making (Buch 2012). Overcoming these challenges may require changing norms and management practices that go beyond the forestry sector. Successful strategies have included participatory consultations to discuss gender gaps in forest policies and practices, creating gender working groups and learning networks, taking gender-transformative research approaches, re-engineering management structures and setting up gender-sensitive monitoring and evaluation systems (Buchy 2012; WOCAN. 2016).

Back to top

Illustrative Country Study

Recently, some technical support provided to China points to the importance of clarifying gender-related issues in forestry investments. While the WBG has a strong commitment to gender issues, forestry operations are often focused on environmental or household-level outcomes, making it difficult to tease out differences in impacts on women and men. An exception is China’s recent land tenure reform, which granted new land tenure rights to over 90 million farming households, covering around 184 million ha of forest land between 2008 and 2014 (World Bank 2016c).

Gender related work

Under the Forests and Poverty Program, PROFOR also provided support for gender-related research. A portfolio review assesses the existence of gender analysis in World Bank projects. An annotated bibliography on gender was also prepared as part of this work to report how gender issues are dealt with in research and project implementation.

The PROFOR -funded Catalyzing Gender-Forests Actions program shares knowledge of practices that are generating gender-responsive forest projects, programs and investments. The goal is to influence and see improved project and program design and implementation of gender ‘best practices’ across the WBG and with its clients and partners, leading to projects that are more inclusive and able to measure improved equity impacts. The underlying theory of change of this work is that through greater awareness of the relative lack of targeted gender efforts in many forests projects and programs, and a better understanding of the kinds of actions that can be undertaken, project teams will include gender-targeted investments and actions in their plans from the outset, starting at the design stage.